The Jester recently met with two members of LTAY to talk about their campaign. Evelien is a recent graduate who launched the campaign in Wageningen last summer. As she felt that discussions around sexual violence were lacking at WUR, Amnesty’s campaign was the perfect opportunity for her to get involved. With a little training from Amnesty and a lot of passion, Evelien gathered some friends to launch the campaign; Judith was one of them. With a group of now 8 people, they’ve been campaigning to ensure that sex based on equality, open communication, and consent is the norm, and start a dialogue about sex and consent among young people.

The LTAY campaign was started by Amnesty. Could you describe what issues this campaign wants to address?

E – This campaign started by addressing the current Dutch law regarding sexual violence and rape, which is very old fashioned and not inclusive of what sexual violence could look like. For example, they don’t consider the possibility of victims being passed out or frozen in fear. We believe this must change because it doesn’t acknowledge victims’ experiences and it makes legal consequences difficult. The group supported the lobbying of Dutch politicians and sent thousands of postcards to the Minister of Justice to put pressure on the government. This Spring, a bill to modernise the law finally came out (it hasn’t been passed yet because we don’t have an official government).

“By opening the conversation, we hope everybody will reflect more on their behaviour”

These laws also have a big impact on cultural awareness, which our campaign also focuses on. After the bill was proposed, we decided to focus on the lack of prevention, support, and attention given to the topic in higher education. Amnesty recently published a study that clearly showed many people go through a form of sexual violence in their time as a student, and in general between the ages of 18-25 years.

The study you mentioned found that 11% of females and 1% of males experienced sex without their consent during college. How can we make sense of these numbers?

E – I think it’s important to realise that for each 10 women you know, one of them has been through this, which means you very likely know perpetrators too. The 1% for men is also high. We also need to keep in mind that some people may have trouble recognising what they’ve been through and that, for men especially, taboos around unwanted sex make it even harder to speak up. These numbers represent people who have identified what they’ve been through as sexual violence and are able to speak up and acknowledge it.

Do you think the definition of consent is universal?

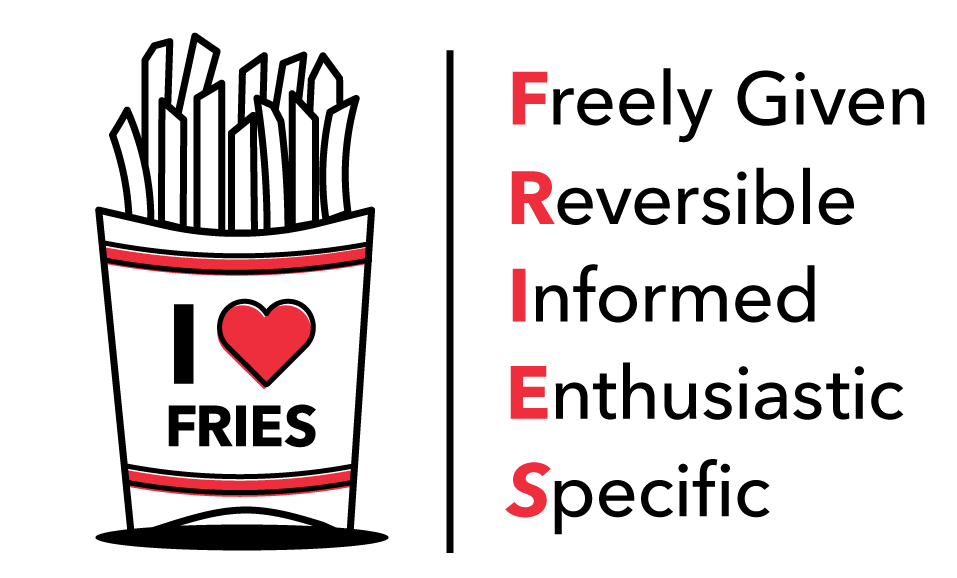

J – Of course, people have their personal ways of how they like to be asked for consent or how they give consent. But there are certain aspects that need to be there for consent and I believe those are universal. They can be summarized in FRIES: Freely given, Reversible, Informed, Enthusiastic and Specific.

E – What we see as universal is that consent has to be actively saying yes to something. There are still a lot of people that view the absence of a no as a yes. This would usually not be the case in other (non-sexual) situations. If you make someone food that they didn’t ask for, do you expect them to eat it?

But it can be very hard to know what another person wants, let alone understanding what you want for yourself. Does this not mean that consent often lies in a grey area?

E – There is a grey area, but we need to be more aware of it and not simply look the other way or ignore it because it’s too complicated. There are instances where it can be hard to know what the other person wants (and to know what you want!), and maybe you cross someone’s boundaries… and that’s bad, but the world isn’t divided between abusers and non-abusers. We need to have better conversations about this for everyone’s sake. We also need to realise that there are so many complexities involved in sexual relations; to understand the sort of expectations and pressure people might deal with in relation to someone else, as well as people’s personal history. People might feel expected to be intimate with someone because they are dating or are married, for example.

“Would you like me to touch you here? Does this feel good? What would you like me to do? are spontaneous ways of asking if the other person is okay.

J – In our campaign, we also find it important to be sex positive. We want to go against the shame and taboos around sex. We support people exploring their sexuality. They may run into their boundaries in this process. We believe that opening the conversation about this allows people to explore in a safe way. We do not want to ‘police’ sex, but by opening the conversation, we hope everybody will be more reflective of their behaviour.

In discussions around consent, affirmative consent has been proposed as a solution. This entails that the person who initiates sexual contact must receive clear permission from the other person before engaging in sexual activity – and that consent must be ongoing throughout the sexual encounter. Do you think this is the way forward?

E – I would say that consent doesn’t need to be as strict as saying “Yes I consent”, but there has to be no doubt that everyone involved wants to have sex. This can happen in a more natural way, like asking someone if they are enjoying something, want to keep going, or whether they want to stop.

“There are still a lot of people that view the absence of a no as a yes.”

J – You also need to keep in mind that even if someone says “Yes I consent” at the beginning of sex, you still have to check that your partner is still enjoying it throughout. A moment of verbal affirmation at the beginning isn’t enough.

A problem I see with affirmative consent is that it requires people to be explicit about what they want. Often though, many people, especially women, find saying no difficult. How can we know that the other person really means what they say, and who’s responsibility is it to know that?

E – I think that it’s the responsibility of everyone involved. As we discussed before, a person doesn’t need to explicitly say no, but it’s still their responsibility to know, for themselves, what they want. That doesn’t mean that if something happens, it’s their fault, but it’s part of having a healthy sex life and enjoying intimacy to get to know your own boundaries and feel empowered to say no. There’s also the aspect of, as a partner, knowing what your bed partner struggles with. This is harder if you don’t know each other well, but you can always check in with each other. It’s complicated because people may feel internalised pressure to act in a certain way or may struggle to express themselves, but there are definitely ways to improve these situations and support one another in expressing ourselves openly and honestly.

J – I don’t think things will ever be perfect. But starting to talk about this topic can make a difference. If two people are having sex and one notices that the other seems distant, then their bed partner asking them “Are you fine? Do you actually like this?” can go a long way. I feel that people often think that only men have to ask women for consent, which is not true. Since starting this campaign, I am more aware of asking my male sex partners for their consent. I also notice that by asking for consent yourself, others also become more aware of this.

“WUR should play a part in building a culture that is more based on consent”

E – We also need to be aware that, though they may not feel like a boundary was crossed, there can be so much pressure on men to perform because of societal expectations. They’re often expected to initiate everything and to always want to have sex.

Could you give some tips & tricks on how someone could ask for another person’s consent in a way that is spontaneous and doesn’t “ruin the moment”?

J – That is a good question. It’s good to share more practical advice with each other.

E – Proposing things is good – “Would you like me to touch you here?” doesn’t feel so stiff and this can be asked spontaneously. “Does this feel good?”, “What would you like me to do?”. Someone’s answers to these questions also indicate whether they are into it or not – rather than ruining the moment, this sort of interaction can make the experience better for everybody.

J – During sex you can ask questions like “Are you still enjoying it?”, “Do you want it more sweet or more rough?” or “What would you like to do now?”. Related to the pressure that men often feel to perform, if you notice your partner is tired, you could propose an alternative, like touching, kissing and cuddling a bit.

Coming back to LTAY, your group of students has taken on the responsibility of raising awareness of these issues. What role do you think WUR should play in this?

E – I feel that the university has its part to play in informing people about consent, whether they take that on themselves or facilitate other actions, especially at the beginning of (student) life at WUR, putting everyone on the same level of understanding in a culturally-sensitive way. Like any institution, WUR should play a part in building a culture that is more based on consent. Letting everyone at the university, especially new students and staff, know where to go for information or support in case they need it, would be an important start. There is plenty of information out there. Being upfront about these issues already raises awareness on the topic and gets the conversation going. As soon as there is visible support, people also feel taken seriously.

J – LTAY has recently released a manifesto that clearly outlines the steps that Amnesty expects of higher education institutes. We aim for all higher education institutes in NL to sign it. It’s available on the LTAY website.

Where can students who have been a victim of sexual assault or want to talk about this issue currently go on campus for support?

E – There are confidential advisers for these issues. However, it is not clear what going to one of these advisers entails, or how these advisers have been trained. We’re not suggesting that the university isn’t capable of providing support, but it is currently unclear what this support looks like. I usually recommend the national hotline from the centre of sexual violence (Centrum Seksueel Geweld); they are available 24/7. Sense.info is a good platform if you want to talk about topics like sex and consent in non-emergency situations.

J – For support at WUR, we will be working on making it more clear for students and staff where they can go and what help they can get in this coming academic year. More to come!

Follow LTAY-Wageningen on Facebook and Instagram @ltaywageningen, or contact them at consentwageningen@gmail.com.